PROJECT DETAILS

- Research Name Laboratory Quality Control

- Category Process

- Location Vilnius, Lithuania

Beyond Mixing: Mastering Ultrasonic Deagglomeration and Particle Dispersion

Executive Summary: Dispersion is not dissolving; it is the mechanical disruption of agglomerates held together by Van der Waals forces. Success depends on finding the "process sweet spot"—too little energy fails to deagglomerate, while excessive processing causes defect formation.

1. The Science: Breaking the Van der Waals Barrier

The utilization of high-intensity ultrasound in fluid processing represents a paradigm shift from macroscopic mechanical mixing to microscopic energy manipulation. While standard mixing moves fluids around particles, Ultrasonic Dispersion targets the forces between them.

1.1 The Mechanism of Action

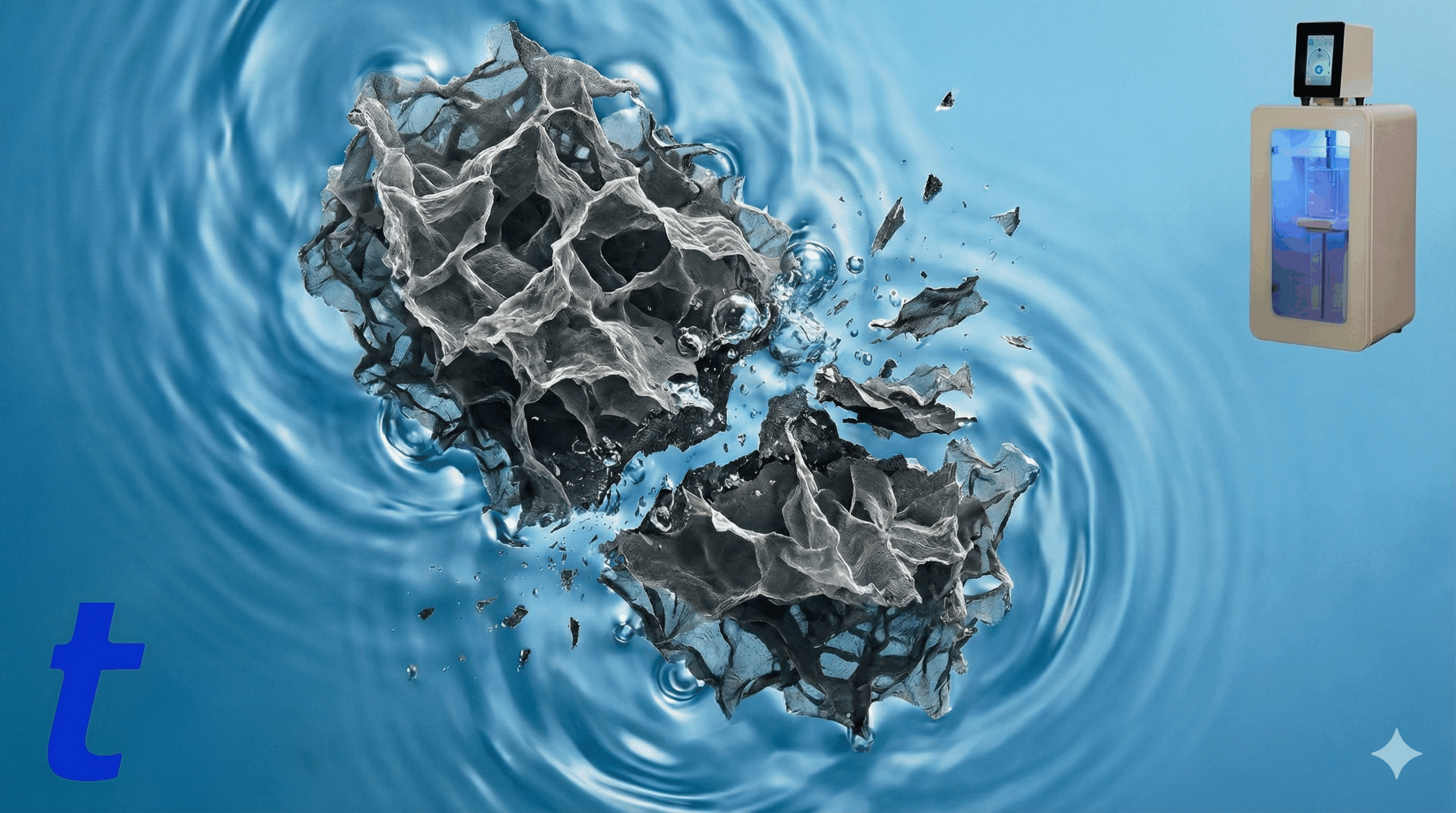

In the context of solid-liquid dispersion, the primary driver is Transient (Inertial) Cavitation. Under high acoustic intensity, bubbles grow explosively and collapse violently. This collapse generates shockwaves and high-speed liquid jets. When these shockwaves propagate through a medium containing suspended solids (such as Carbon Nanotubes or metal oxides), they induce two specific mechanical effects:

- Inter-particle Collision: The turbulence accelerates particles into one another at high velocities, shattering agglomerates.

- Shear Forces: In layered materials like graphite, shockwaves induce shear along the basal planes, overcoming the Van der Waals forces (≈ 68 mJ/m² for graphene).

1.2 Case Study: The "Sweet Spot" in Nanomaterial Synthesis

Achieving a stable dispersion is a delicate balance. Recent studies on Liquid Phase Exfoliation (LPE) of graphene reveal that the "more power, longer time" approach is scientifically flawed.

Impact of Sonication Time on Material Defects

Lower bar = Better Quality (Lower Defect Ratio)

| 10 Mins |

High Defects (Under-processed)

|

| 20 Mins |

Optimal (Sweet Spot)

|

| 30 Mins |

Re-stacking / Fragmentation

|

Optimal Processing: Research identifies an optimal sonication time of roughly 20 minutes for specific volumes. At this point, the ratio of defects is minimized. Extending beyond this window degrades quality, as thermodynamics eventually favor re-stacking.

1.3 Concrete and Macro-Scale Dispersion

Dispersion is not limited to graphene. In the construction industry, dispersing nano-silica (SiO2) into cement paste is critical. A protocol of just 5 minutes at 40 kHz can deagglomerate these particles, increasing compressive strength by 10-15%.

2. The Gap: Why Traditional "Beaker & Probe" Methods Fail

Many researchers struggle to reproduce dispersion results found in literature. The failure rarely lies in the chemistry, but in the instability of legacy hardware.

2.1 The Power Density Fallacy

A common misconception in scale-up is simply increasing the probe size. However, to maintain the same displacement amplitude (micron level) with a larger surface area, power requirements increase quadratically. Legacy analog systems often lack the feedback loops to maintain this amplitude under varying loads. As viscosity changes, the acoustic impedance (Z) shifts, causing energy delivery to drop significantly.

2.2 Inconsistent Energy Distribution

In a standard batch beaker, acoustic intensity attenuates rapidly with distance from the probe tip (I ∝ 1/r²). This creates "dead zones" where agglomerates remain untouched, resulting in a high Polydispersity Index (PDI).

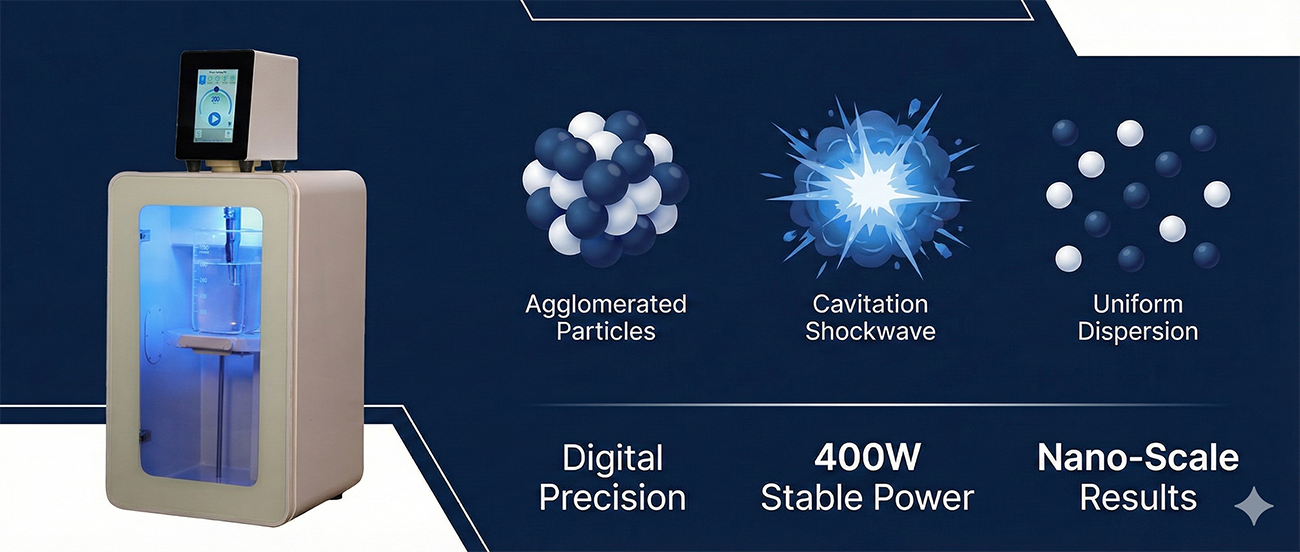

3. The Topsonics Solution: Precision for the Benchtop

At Topsonics, we recognize that dispersion is an exact science, not a brute-force application. Our 400W laboratory homogenizer is engineered to address the specific challenges of solid-liquid interactions.

3.1 Digital Reproducibility

Our system utilizes digital auto-tuning to lock onto the precise resonance frequency of the sonotrode (e.g., 20 kHz ± 100 Hz). This ensures that whether you are dispersing a low-viscosity aqueous solution or a heavy resin, the amplitude remains constant.

"Benefit: You can run a 20-minute graphene exfoliation protocol today and get the exact same defect ratio next month."

3.2 Smart Energy Management

The "Hot Spot" theory dictates that bubble collapse generates temperatures of ~5,000 K. Pulse Mode: The Topsonics interface allows for precise Pulse-Width Modulation (PWM). By allowing the sample to cool between bursts, you maximize cavitation impact while minimizing bulk thermal degradation.

3.3 Optimized Form Factor

We moved away from the "industrial box" aesthetic. Our device features a compact footprint with a modern 5-inch touch display, designed for the crowded academic or R&D workbench.

4. Technical Comparison: Dispersion vs. Mixing

To better understand where ultrasonic processing fits in your workflow, consider the energy density hierarchy:

| Feature | Mechanical Mixing | Topsonics Ultrasonic |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant Mechanism | Turbulence & Macro-Shear | Acoustic Cavitation & Shockwaves |

| Energy Source | Mechanical Impeller | Bubble Implosion |

| Target Particle Size | > 10 microns | < 100 nanometers |

| Solid-Liquid Effect | Suspension | Deagglomeration & Exfoliation |

5. FAQ: Expert Insights on Dispersion

Q: Can I use ultrasound to disperse carbon nanotubes (CNTs) without shortening them?

A: It is a trade-off. Violent cavitation cleans the surface and separates bundles, but excessive energy will fracture the nanotube length. You must find the minimum energy density required for separation. Using a mild surfactant (like Pluronic F127) can lower the energy barrier.

Q: Why does my dispersion re-agglomerate after a few hours?

A: You likely achieved physical dispersion but failed to stabilize the surface. Once the ultrasonic energy stops, Van der Waals forces take over. You need a stabilizer (surfactant or polymer) that adsorbs onto the particle surface during the "Interfacial Shell" phase.

Q: How do I scale up from my beaker to a larger volume?

A: Do not just buy a bigger probe; the physics usually fail. The correct method is Continuous Flow Processing. You pump your fluid through a confined cell where it passes the probe tip, ensuring every particle receives the same specific energy (J/mL).

Next Step

Are you struggling with inconsistent particle sizes or agglomeration in your nanomaterials? Contact our application team today. We can help you calculate the specific energy (J/mL) required for your solid load and determine if the Topsonics 400W system is the right tool to stabilize your dispersion.